- Introduction

- Why not condoms?

- Babies don’t have sex

- He can wait until adulthood and then choose

- Men rarely choose to be circumcised

- No national or international medical association recommends routine infant circumcision

INTRODUCTION

Medical research done over the past decades has provided conclusive evidence that male circumcision has many medical benefits. In fact, both the American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) have endorsed male circumcision for health reasons: in December 2014 the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta made a policy statement strongly supporting circumcision . The new draft guidelines mirror an updated policy on circumcision released by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2012. For further information regarding the CDC Statement, see e.g. the article on Scientific American, and for more on the AAP Statement, see WebMD and CNN.

Medical studies have shown that circumcision greatly reduces the risk of urinary tract infections (UTI), especially in the first year of life. These infections can cause serious problems, especially in infants. For example, UTI can cause scarring of the kidney and ultimately hypertension or kidney failure. To make matters worse, studies have shown that UTI are becoming more resistant to antibiotics, thereby making treatment both much harder and less effective.

Cancer of the penis is virtually non-existent in circumcised men. Of the 60000 cases reported since the 1930´s, fewer than 10 occurred in circumcised men. The risk of penile cancer in uncircumcised men is 1 case per 400-600 men, while in circumcised men it is 1 case per 75000 to 8 million men. Circumcision also helps to reduce the risk of cervical cancer in female partners. Prostate cancer may also be increased for uncircumcised men.

Extensive research done during the past 15 years has convincingly shown that infant circumcision reduces the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS (for further information, see the section on HIV/AIDS: http://circfacts.org/medical-benefits/hivaids/). Scientific studies done over the past 10 years or so have established that circumcision reduces female-to-male HIV transmission rates by around 70%. The medical evidence is now overwhelming. The main question has been how circumcision can best be introduced as a public health policy. International agencies like the United Nations and the World Health Organization have started voluntary male medical circumcision (VMMC) campaigns in e.g. many sub-Saharan countries to save the lives of men and women in regions particularly vulnerable to the spread of HIV. As a result many sub-Saharan countries have undertaken measures to dramatically increase circumcision. These measures have been ongoing for the past few years and have shown many positive effects already. These ongoing efforts to spread circumcision in developing nations in order to curb the spread of HIV are a triumph of common sense, global health initiatives, science, and basic humanity. For further information on VMMC see here.

Circumcision also eliminates problems like phimosis (non-retractable foreskin) and balanitis (inflammation of the foreskin). Even though these problems only occur in about 10% of men, they can be very painful if not treated. In older males, phimosis can cause urine blockage leading to kidney damage. Other painful problems that might occur include paraphimosis (where the retracted foreskin cannot be brought back again over the glans) and posthitis (inflammation of the foreskin). Uncircumcised men are often unaware that these problems are all related to the presence of a foreskin, and that the discomfort and pain that they are experiencing are easily treatable. Often the only permanent treatment is circumcision.

A summary of a risk-benefit analysis of circumcision can be found in the flyer circ-risk-benefits

Intactivists react to this overwhelming body of medical evidence the only way pseudoscientists can – with a seemingly endless parade of misleading, half-true, or even downright bogus arguments. Those relating to risks and complications, and especially to HIV/AIDS, are so numerous they merit separate sub-sections of their own (http://circfacts.org/medical-benefits/risks-complications/ & http://circfacts.org/medical-benefits/hivaids/). The rest are dealt with below.

Why not condoms?

March 2019

A common refrain by circumcision opponents, when confronted with the, now overwhelming, evidence that circumcision protects against a variety of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and HIV in particular, is that men can simply use condoms. No need to be circumcised! Besides, circumcision has only a partially protective effect, so circumcised men still need to use condoms anyway. So, what is the point of getting circumcised?

Such reasoning ignores human nature. The problem with behavioural approaches is that they depend on a lifetime of diligent compliance. In reality, no matter how vigorously condoms are promoted, one will never get all men to use them, or use them consistently every time they have sex, or use them properly every time they do. Men simply don’t like them. In fact, some dislike them to the point that they surreptitiously remove them when their partner isn’t looking, a disgraceful practice known as “stealthing” (Brodsky, 2017).

Condoms have been heavily promoted as part of the anti-HIV drive in developed and developing countries alike. They are the “C” in the “ABC” approach: Abstinence, Be faithful, Condoms. But results have been disappointing. In some instances the problems have been practical. People living in remote rural communities may be a long walk away from the nearest supply, but they only have to access a mobile circumcision clinic once and they are (partially) protected for life. A lifetime of partial protection is better than none at all.

But even in urban areas, accessibility may be limited. A study in Lilongwe, the capital of Malawi, found problems with limited outlets, poor visibility, and cost, the last mattering in a country with an average annual income of only $800 (Shacham et al., 2015).

The original “ABC” approach has been tried since the 1980s, but is failing. Global HIV prevalence continues to rise. Abstinence and faithfulness have been a complete flop. Programs depending on these approaches, beloved of the religious right and the Catholic Church, have proved useless (Lo et al., 2016).

Condoms do help, but are proving insufficient. For example, in a study of four African countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Swaziland, Tanzania and Zambia) the researchers “found no convincing evidence that condom users were less likely to be HIV-infected than people who reported not using condoms” (Hearst et al., 2013).

A Cochrane Review of seven randomized controlled trials (the so-called “gold-standard” of epidemiology), four in Africa, two in the USA, and one in the UK, concluded “We found few studies and little clinical evidence of effectiveness for interventions promoting condom use for dual protection” against pregnancy and STIs (Lopez et al., 2013).

No one denies that, used consistently and properly, condoms are effective but, as is apparent from real-world data, the ideal of consistent and proper use by all sexually active men will never be achieved. But, even when they are used consistently, they are not as effective as one might imagine. One can cite laboratory tests that indicate near 100 % impermeability to HIV, and a few studies of serodiscordant couples in ideal settings that give good results. But when all the real-world evidence is reviewed the picture is not as good. A Cochrane Review found that, in practice, condoms are only about 80 % effective at blocking heterosexual HIV transmission (Weller & Davis-Beaty, 2002). A more recent review and meta-analysis found them to be only 71 to 77 % effective, slightly better at stopping male to female, than female to male, transmission (Giannou et al., 2015).

Figures of 71-77 %, or 80 %, are not much better than the effectiveness of circumcision, although unlike circumcision, the protection afforded by condoms works in both directions, whereas circumcision directly protects only the man. The latest meta-analyses indicate that the initial, and much touted, 60 % protection against heterosexual HIV acquisition in men indicated by the African circumcision trials is an underestimate. The recent meta-analyses found 70 % (Lei et al., 2015) and 72 % (Sharma et al., 2018). Circumcision provides back-up for the 20 % or more times that condoms fail, as well as for those who don’t use condoms consistently, or at all, for whatever reason.

Condoms are even less effective against HPV. Tobian et al. (2012) found that condom use did not protect against high-risk (oncogenic) HPV infection on the coronal sulcus (where the glans meets the shaft). This may be partly due to inconsistent condom use, but they also pointed to the highly mobile nature of this virus – it can transfer readily from one genital site to another and not all these sites (e.g., the scrotum) are covered by a condom. Circumcision, it should be noted, is partially protective against oncogenic HPV.

Nevertheless, despite these shortcomings, condoms are recognised by the WHO as a vital part of its anti-HIV strategy, but not when used alone. When used in conjunction with other approaches they can make a difference. The three most effective strategies are now recognised as anti-retroviral therapy (ART), condoms and circumcision. All have their drawbacks. Behavioral approaches (e.g., condoms, fidelity and abstinence), and circumcision, were discussed above. ART requires daily administration, life-long commitment, has unpleasant side-effects, creates resistant strains of the virus, and is expensive. Its deployment also leads to an increased population prevalence of HIV, as people who formerly would have died of AIDS-related illnesses, are now living with HIV (Zaidia et al., 2013). They are, however, much less infectious, providing they keep taking the medication. ART can therefore reduce incidence (i.e., new infections) but at a cost.

Each approach on its own has only a limited effect. But when combined there is a greater likelihood of success. An analogy is air bags and seat belts. Air bags, like circumcision, are there all the time. Seat belts, like condoms, have to be put on each time. Neither provides complete protection in the event of an accident, but used together protection is maximized.

And we now have real world data showing that this combination approach is working. Where circumcision is being rolled out, alongside these other approaches, HIV incidence is falling in Uganda (Kong et al. 2016; Gabrowski et al., 2017) and in South Africa (Auvert et al., 2013). The effect is more noticeable in men, for whom circumcision is directly protective.

So, the short answer to the intactivists’ refrain, “Why not condoms?” is that on their own they are insufficient. Something more is needed and the evidence shows that the “something more” is ART and circumcision. The new “ABC” is Anti-retrovirals, Behaviour, Circumcision. All three are vital.

References

Auvert, B., Taljaard, D., Rech, D., Lissouba, P., Singh, B., Bouscaillou, J., Peytavin, G., Mahiane, S.G., Sitta, R., Puren, A., Lewis, D. (2013) Association of the ANRS-12126 male circumcision project with HIV levels among men in a South African township: Evaluation of effectiveness using cross-sectional surveys PLoS Med., 10(9), e1001509. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001509

Brodsky, A. (2017) “Rape-adjacent”: Imagining legal responses to non-consensual condom removal. Columbia J. Gender Law, 32(2), 183-210. https://cjgl.cdrs.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2017/04/Brodsky_Final_PRINT.pdf

Gabrowski, M.K., Serwadda, D.M., Gray, R.H., Nakigozi, G., Kigozi, G., Kagaayi, J., Ssekubugu, R., Nalugoda, F., Lessler, J., Lutalo, R.M., Galiwango, F., Makumbi, X., Kong, D., Kabatesi, D., Alamo, S.T., Wiersma, S., Sewankambo, N.K., Tobian, A.A.R., Laeyendecker, O., Quinn, T.C., Reynolds, S.J., Wawer, M.J., Chang, L.W. (2017) HIV prevention efforts and incidence of HIV in Uganda. New Eng. J. Med., 377(22), 2154-66. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1702150

Giannou, F.K., Tsiara, C.G., Nikolopoulos, G.K., Talias, M., Benetou, V., Kantzanou, M., Bonovas, S., Hatzakis, A. (2015) Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission: a systematic review and metaanalysis of studies on HIV serodiscordant couples. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 16(4), 489-99. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1586/14737167.2016.1102635 (Abstract only).

Hearst, N., Ruark, A., Hudes, E.S., Goldsmith, J., Green, E.C. (2013) Demographic and health surveys indicate limited impact of condoms and HIV testing in four African countries. African J. AIDS Res., 12(1), 9-15. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2989/16085906.2013.815406

Kong, X., Kigozi, G., Ssekasanyu, J., Nalugoda, F., Nakigozi, G., Ndyanabo, A., Lutalo, T., Reynolds, S.J., Ssekugugu, R., Kagaayi, J., Quinn, T.C., Serwadda, D., Wawer, M.J., Gray, R.H. (2016) Association of medical male circumcision and antiretroviral therapy scale-up with community HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. JAMA, 316(2), 182-90. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5027874/

Lei, J.H., Liu, L.R., Wei, Q., Yan, S.B., Yang, L., Song, T.R., Yuan, H.C., Lu, X., Han, P. (2015) Circumcision status and risk of HIV acquisition during heterosexual intercourse for both males and females: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0125436. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0125436

Lo, N.C., Lowe, A., Bendavid, E. (2016) Abstinence funding was not associated with reductions in HIV risk behavior in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Affairs, 35(5), 856-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27140992 (Abstract only).

Lopez LM, Otterness C, Chen M, Steiner M, Gallo MF. (2013) Behavioral interventions for improving condom use for dual protection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 10. Art.No.: CD010662. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010662.pub2. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010662/full

Shacham, E., Thornton, R., Godlonton, S., Murphy, R. Gilliland, J. (2015) Geospatial analysis of condom availability and accessibility in urban Malawi. Int. J. STD. AIDS, 27(1), 44-50. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956462415571373?journalCode=stda

Sharma, S.C., Raison, N., Khan, S., Shabbir, M., Dasgupta, P., Ahmed, K. (2018) Male circumcision for the prevention of HIV acquisition: A meta-analysis. BJU Int., 121(4), 515-26. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bju.14102

Tobian, A.R., Kigozi, G., Gravitt, P.E., ChangChang, X., Serwadda, D., Eaton, K.P., Kong, X., Wawer, M.J., Nalugoda, F., Quinn, T.C., Gray, R.H. (2012) Human papillomavirus incidence and clearance among HIV-positive and HIV-negative men in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS, 26, 1555-65. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3442933/

Weller SC, Davis-Beaty K. (2002) Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003255. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003255. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003255/full

Zaidia, J., Grapsaa, E., Tansera, F., Newella, M-L, Barnighausen, T. (2013) Dramatic increases in HIV prevalence after scale-up of antiretroviral treatment: a longitudinal population-based HIV surveillance study in rural kwazulu-natal. AIDS, 27(14), 2301-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4264533/

Babies don’t have sex

Stephen Moreton, Ph.D.

Last updated April 2020.

The argument takes various forms, sometimes as in the title above, employed by prominent intactivist Joseph Lewis (2017), sometimes more indirectly, as in “children are not at risk of STIs” (Earp & Darby, 2015), and “little babies simply aren’t the at-risk population when it comes to sex-related diseases” (Earp, 2011). The idea is that because infants and children are not sexually active they do not need circumcision. It can be deferred until later. Intended as a reason to wait until adulthood if circumcision is proposed as prevention for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in general or HIV in particular, this argument, when looked at rationally, actually backfires rather badly on the intactivists.

Achieving high circumcision rates is vital in HIV epidemic settings. Accordingly, a great deal of research has been done to ascertain what factors increase acceptability of the procedure, and which deter men from having it done. Any deterrent means fewer circumcisions, and hence more men at risk. One of the deterrents, or barriers, is the need to abstain from sex during healing. Six weeks is the recommended time, eight if a suture-free device (such as Prepex) is being used. The man may not even be able to masturbate for around three to four weeks, and erections may still be painful at three weeks: “Participants generally reported no sexual activity in the first three weeks with some painful erections towards week three. Some reported masturbatory activities and oral sex from week four and there were a few who reported incidences of penetrative sex at weeks five and six” (Toefy et al., 2015).

Many men struggle to last that long! The longer they go without sexual relief, the “hornier” they get, and the more erections they must endure, stretching the wound around their penis. Meantime, their female partners might also grow frustrated. Some men express fears that their partners will stray as a result, or that the enforced celibacy might put strains on their relationships.

The need for sexual abstinence during healing is not the only barrier, and not always the main one, but it is a major one, along with the related fear of having an erection during the healing period. Whilst babies can have erections, they are not likely to be as common as in sex-starved men impatiently waiting for their freshly cut penis to heal. The need for sexual abstinence (both for themselves and their partners) and the fear of having erections are cited as deterrents to circumcision by youths and men, or their female partners, in the following studies (with quotes from those studies):

Need for sexual abstinence:

Chiringa et al. (2016): 58.5 % of men feared “losing my partner or wife during the waiting period”.

Evens et al. (2014): “The most common secondary barrier was the post-procedure abstinence period”.

George et al. (2014): “there was a concern that boys would not abstain from sex during the six-week healing process because of pressure for sex from their girlfriends”.

Gonzales et al. (2012): “The most traumatic thing could be not having sex during the post-operative period.”

Hatzold et al., (2014): “older men felt that the waiting time before resumption of sex post VMMC (six weeks) was too long”

Herman-Roloff et al. (2011): “some participants who knew the recommended duration of the abstinence period reported that six weeks was too long to abstain from sexual intercourse”

Khumalo-Sakutukwa et al. (2013): “Older men indicated that they would be reluctant to defer sexual contact during the healing period post-circumcision”.

Maibvise, C., & Mavundla, T.R. (2014): “This has left the waiting period for healing as the only stressor for impatient highly sexually active men.”

Moyo et al. (2015): “The 6-week recovery period that is accompanied by abstinence was additionally unacceptable to study participants.”

Nevin et al. (2015): “Respondents in all FGDs [focus group discussions] reported that the long period of abstinence following a circumcision was a negative aspect of the procedure.”

Plotkin et al. (2013): “Concerns about a wife seeking another partner during the abstinence period were less of an issue among older/married men but were widely noted among participants… Women also expressed concerns about abstinence but thought that their men would not be able to abstain”.

Ssesekubugu et al. (2013): “Many participants, particularly decliners, believed this period was too long for them to wait to resume sexual intercourse” … “Men were also concerned about the possibility that their spouses would become sexually involved with other men during the wound-healing abstinence period”.

Zamawe & Kusamula (2015): “Almost all participants cited the 6-week post-circumcision sex abstinence period as a major barrier to adoption of circumcision… They reasoned that it is difficult to sleep together with their partners on the same bed for such a long period, without being tempted to have sex. … their wives did not approve it upon hearing that the wound would take up to 6 weeks to heal.”.

Nakyanjo et al. (2019): “Some women felt this [sexual abstinence during healing] was a burden, especially for married couples. Women said some couples engaged in sex before complete wound healing due to the female partner’s impatience.”.

Nanteza et al., (2019): “Sexually active men said that the required six weeks of sexual abstinence after circumcision were too long.”

Fear of erections:

Bailey et al. (2002): “A frequently expressed concern regarding post-pubertal ages was the pain that adolescent boys and young men would feel if they had an erection while healing.”

Chiringa et al. (2016): “The results of the study indicated fear of loss of capability of having an erection after circumcision as well as having an erection during waiting period as a major barrier for circumcision as reflected by 222 (95%) respondents.”

Evens et al. (2014): “Concern over pain during morning erections was another common concern.”

Ngalande et al. (2006): “Pain as part of the healing process was seen as of equal or even greater concern than pain during the procedure itself, especially in post-pubertal boys who are likely to have frequent erections.”

Plotkin et al. (2013): “participants described a fear of erections causing stitches to rupture, resulting in pain and delayed wound healing.”

Skolnik et al. (2014): “Fear of erections as a cause of pain in the weeks following circumcision was emphasized in all four FGDs, and some participants even requested a medication to prevent erections.”.

If the need for sexual abstinence, and the related problem of unwanted erections in virile young men, is not enough there is another sex-related reason for why infant circumcision is preferable to adult: the risk of STIs. If a man has an unhealed wound on his penis one hardly needs a medical degree to realise that this will put him at greater risk if his sexual partner has HIV, or other STIs. This is precisely the reason why men are strongly advised to wait until wound healing is complete before resuming sexual intercourse. But the danger goes both ways. If the man is already HIV positive, then having an unhealed wound on his penis puts his female partners at greater risk of infection too (Wawer et al., 2009). Impatient, sex-starved men resuming sex before they have fully healed has been identified as a significant problem in several studies (Toefy et al. 2015), a problem that would not arise if they were circumcised as infants.

Thus, the refrain, “Babies don’t have sex”, is actually an argument for infant, rather than adult, circumcision.

References

Bailey, R.C., Muga, R., Poulussen, R., Abicht, H. (2002) The acceptability of male circumcision to reduce HIV infections in Nyanza Province, Kenya, AIDS Care, 14(1), 27-40. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11798403

Chiringa, I.O., Ramathuba, D.U. Mashau, N.S. (2016) Factors contributing to the low uptake of medical male circumcision in Mutare Rural District, Zimbabwe. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 8(2), e1-6. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4913440/

Earp, B.D. (2011) Is the non-therapeutic circumcision of infant boys morally permissible? Blog post: http://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2011/08/circumcision-is-immoral-should-be-banned/

Earp, B.D., Darby, R. (2015) Does science support infant circumcision? The Skeptic, 25(3), 23-30. on-line: https://www.skeptic.org.uk/magazine/onlinearticles/infant-circumcision/

Evens, E., Lanham, M., Hart, C., Loolpapit, M., Oguma, I., Obiero, W. (2014) Identifying and addressing barriers to uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision in Nyanza, Kenya among men 18–35: A qualitative study. PLoS One, 9(6), e98221. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4047024/

George, G., Strauss, M., Chirawu, P., Rhodes, B., Frohlich, J., Montague, C., Govender, K. (2014) Barriers and facilitators to the uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) among adolescent boys in KwaZulu–Natal, South Africa. African J. AIDS Res., 13(2), 179-87. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25174635

Gonzales, F.A., Zea, M.C., Reisen, C.A., Bianchi, F.T., Rodríguez, C.F.B., Pardo, M.A., Poppe, P.J. (2012) Popular perceptions of circumcision among Colombian men who have sex with men. Cult. Health Sex., 14(9), 991-1005. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3463718/

Hatzold, K., Mavhu, W., Jasi, P., Chatora, K., Cowan, F.M., Taruberekera, N., Mugurungi, O., Ahanda, K., Njeuhmeli, E. (2014) Barriers and motivators to voluntary medical male circumcision uptake among different age groups of men in Zimbabwe: Results from a mixed methods study. PLoS One, 9(5):e85051. On-line: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0085051

Herman-Roloff, A., Otieno, N., Agot, K., Ndinya-Achola, J., Bailey, R.C. (2011) Acceptability of medical male circumcision among uncircumcised men in Kenya one year after the launch of the national male circumcision program. PLoS One, 6(5), e19814. On-line: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0019814

Khumalo-Sakutukwa, G., Lane, T., van-Rooyen, H., Chingono, A., Humphries, H., Timbe, A., Fritz, K., Chirowodza, A., Morin, S.F. (2013) Understanding and addressing sociocultural barriers to medical male circumcision in traditionally noncircumcising rural communities in sub-Saharan Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(9), 1085-100. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3810456/

Lewis, J. (2017) MEDICAL FRAUD: First Choice Pediatrics Brazenly Misquoting AAP to Push Circumcision. Blog post: http://joseph4gi.blogspot.co.uk/2017/07/medical-fraud-first-choice-pediatrics.html

Maibvise, C., Mavundla, T.R. (2014) Reasons for the low uptake of adult male circumcision for the prevention of HIV transmission in Swaziland. African J. AIDS Res., 13(3), 281-9. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25388982

Moyo, S., Mhloyi, M., Chevo, T., Rusinga, O. (2015) Men’s attitudes: A hindrance to the

demand for voluntary medical male circumcision – A qualitative study in rural Mhondoro-Ngezi, Zimbabwe. Global Public Health, 10(5-6), 708-20. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25648951

Nakyanjo, N., Piccinini, D., Kisakye, A., Yeh, P.T., Ddaaki, W., Kigozi, G., Gray, R.H., Kennedy, C.E. (2019) Women’s role in male circumcision promotion in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Care, 31(4), 443-450. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6335195/

Nanteza, B.M., Makumbi, F.E., Gray, R.H., Serwadda, D., Yeh, P.T., Kennedy, C.T., (2019) Enhancers and barriers to uptake of male circumcision services in Northern Uganda: a qualitative study, AIDS Care, ePub ahead of print. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31795737

Nevin, P.E., Pfeiffer, J., Kibira, S.P.S., Lubinga, S.J., Mukose, A., Babigumira, J.B. (2015) Perceptions of HIV and safe male circumcision in high HIV prevalence fishing communities on Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS One, 10(12), e0145543. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4686987/

Ngalande, R.C., Levy, J., Kapondo, C.P.N., Bailey, R.C. (2006) Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV infection in Malawi. AIDS Behav., 10(4), 377-85. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16736112

Plotkin, M., Castor, D., Mziray, H., Küver, J., Mpuya, E., Luvanda, P.J., Hellar, A., Curran, K., Lukobo-Durell, M., Ashengo, T.A., Mahler, H. (2013) “Man, what took you so long?” Social and individual factors affecting adult attendance at voluntary medical male circumcision services in Tanzania. Glob. Health Sci. Pract., 1(1), 108-16. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4168557/

Skolnik, L., Tsui, S., Ashengo, T.A., Kikaya, V., Lukobo-Durrell, M. (2014) A cross-sectional study describing motivations and barriers to voluntary medical male circumcision in Lesotho. BMC Public Health, 14(1119). On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4287583/

Ssesekubugu, R., Leontsini, E., Wawer, M.J., Serwadda, D., Kigozi, G., Kennedy, C.E., Nalugoda, F., Sekamwa, R., Wagman, J., Gray, R.H. (2013) Contextual barriers and motivators to adult male medical circumcision in Rakai, Uganda. Qual. Health Res., 23(6), 795-804. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23515302

Toefy, Y., Skinner, D., Thomsen, S.C. (2015) “What do You Mean I’ve Got to Wait for Six

Weeks?!” Understanding the sexual behaviour of men and their female partners after voluntary medical male circumcision in the Western Cape. PLoS One, 10(7), e0133156. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4503729/

Wawer, M.J., Makumbi, F., Kigozi, G., Serwadda, D., Watya, S., Nalugoda, F., Buwembo, D., Ssempijja, V., Kiwanuka, N., Moulton, L.H., Sewankambo, N.K., Reynolds, S.J., Quinn, T.C., Opendi, P., Laeyendecker, O., Gray, R.H. (2009) Circumcision in HIV-infected men and its effect on HIV transmission to female partners in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 8(3), 170-8. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2905212/

Zamawe, C.O.F., Kusamula, F. (2015) What are the social and individual factors that are associated with undergoing male circumcision as an HIV prevention strategy? A mixed

methods study in Malawi. Int. Health, 8(3), 170-8. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26503362

He can wait until adulthood and then choose

March 2018

At first glance this seems a very reasonable position. It hands the decision to the person concerned, and so solves the issue of consent at a stroke. Consequently, this argument is near ubiquitous in debates on circumcision. But it is based on ignorance coupled to an ideological obsession with “bodily autonomy”. If our predecessors had applied it to vaccination we’d still have smallpox. If we apply it to circumcision, it would mean more dead people, more sick people and higher health care costs. To understand why, we must first look at what puts people off circumcision in adulthood.

-

Cost

By waiting until the male is old enough to decide for himself if he wishes to be circumcised or not, one is in effect waiting until he cannot afford it. Costs vary from provider to provider, but one only needs approximate figures to make the point. In the U.S. an infant circumcision costs around $150 – $400, an adult one about $800 – $3,000 depending on medical factors, and type of anaesthesia (http://health.costhelper.com/circumcision.html ). In the U.K. prices are similar, only in £s, as a search of clinics offering the procedure will show. Essentially, in developed countries an adult circumcision can cost up to about ten times an infant one.

Costs are much lower in developing countries, but the same principle applies: adult circumcision is more expensive than infant circumcision. For example, in Rwanda, an infant circumcision costs about $15, an adult one $59, and the procedure is hugely cost-saving in a country with 3 % HIV prevalence (low by African standards) (Binagwaho et al. 2010). In resource-limited settings this is very important. Money saved by circumcising infants rather than adults is money available for other life-saving purposes.

Even in countries where circumcision is offered free of charge, as part of the WHO anti-circumcision program, there is still a cost to the patient. He may incur travelling expenses getting to the clinic, and he will have to take time off work while he recovers. A few hardy souls may return promptly, but in doing so they risk injury, such as the wound opening up. Stitches may snag on clothing, or the various clips and bands used in suture-free devices may come loose. Time off work means lost earnings which, to a poor person, may be unacceptable.

-

Risk

There is a window of opportunity in early infancy when circumcision is safest. After that time, the baby enters a phase called mini-puberty. A surge of androgens causes the foreskin to thicken and vascularize. The risk of complications, such as bleeding, then rises. In the largest study of its kind, with a sample size of 1.4 million, researchers, mostly from the CDC, studying circumcision in the U.S.A., found that the risk of complications rises 10- to 20-fold after infancy. But for infants, risk of an adverse event is only 0.4 %, and these are mostly minor things, easily and completely remedied (El Bcheraoui et al. 2014).

-

Inconvenience

An adult has to take time off work, studies, sports and/or other activities. In short getting circumcised is disruptive.

-

Need for abstinence from sex

This is a major deterrent for many men and youths. They cannot even masturbate for a few weeks, let alone have sex. Many feel they cannot last that long, or that their female partners will complain. This is discussed in detail in the section “Babies don’t have sex”: http://circfacts.org/general-information/#med2

-

Fear of pain

The genitals are a sensitive area, and cutting them is bound to hurt. Local and general anaesthesia are highly effective. The latter is risky for infants, for whom local anaesthetic is now standard practice, but it tends to be used for older children who otherwise may not stay still during the procedure. General anaesthetics carry more risks, and can have unpleasant side effects, such as nausea and vomiting. Whilst the pain of the actual procedure can be very effectively controlled, there is still the aftermath to consider.

For an infant healing takes just 1 to 2 weeks, but for an adult at least 4 weeks, sometimes more (6 weeks sexual abstinence is recommended, 8 for suture-less devices like Prepex). So, an older boy or man has to put up with discomfort for much longer than an infant, and an infant does not have as large a penis (hence a smaller wound) and does not walk around (hence risk stitches etc. snagging on undergarments). And then there is the issue of erections.

Those who argue that the decision should be deferred until adulthood have clearly not experienced an erection with a dozen to twenty stitches holding together a wound all around their penis. Perhaps if they did have this experience, they would understand why many males are reluctant to get circumcised, even if they are positive about the procedure. Erections in babies are much less frequent, and their circumcisions require no stitches. Fear of erections is a commonly cited barrier to adult circumcision (http://circfacts.org/general-information/#med2 ).

-

Embarrassment

Circumcision is an intimate procedure involving sexual organs. Some men may simply feel awkward talking about it. In non-circumcising cultures they may encounter resistance if they approach their physician to request a circumcision without an immediate medical need. A lad may face ridicule or teasing from others if they find out he wishes to be circumcised in a culture where circumcision is unusual.

-

Cosmetic outcome

Cosmetic appearance is subjective, but infant circumcisions are said to result in less scarring than adult ones (Gonzales et al. 2012; Mavhu et al. 2016; Morris et al. 2012). As infant circumcisions use no stitches, they will not have the stitch marks that many a male circumcised in later life will have.

-

Cultural objections

In some places having a foreskin is as much a mark of tribal identity as not having one is in others. Circumcised males may face social stigmatisation. Some may equate it with Islam, and so object on religious grounds. In Swaziland, circumcised males are thought to be less masculine (Adams & Moyer 2015). Superstitions and urban myths deter some men, such as a belief that their severed foreskin may be used in witchcraft (Adams & Moyer 2015; Bulled & Green 2015; Chikutsa & Maharaj 2015). Conspiracy theories, about circumcision being a western plot against Africans also feature (Adams & Moyer 2015). Returning their detached foreskins can counter some of the superstitions, but cultural ones, including social attitudes and religion are much harder to change. These remain difficult barriers to both adult and infant circumcision.

-

Concern about loss of sensitivity or sexual function

If men believe that circumcision will result in a diminution of sexual pleasure it will, understandably, deter them from undergoing the procedure, or giving it to their sons. Little wonder intactivists expend so much energy in promoting this belief. As is evident from the “Function & sensation” section, this fear is baseless, but it remains a barrier nonetheless.

-

Futility

This barrier takes three forms:

a) Not applicable. The man may be in a stable, faithful relationship with his wife whom he is confident is not infected. So he sees no point in taking precautions, because they do not apply to him as he will never be exposed to HIV. This is fair enough, but many young males go through a phase of “playing the field” before settling down with their love. They will still need protection, which circumcision prior to them becoming sexually active will provide.

b) No point. In another form, the argument runs along the lines of, “If you still need to wear a condom even when circumcised, then what is the point of being circumcised?” But this is mistaken, as explained here: http://circfacts.org/general-information/#med1 Condoms are not fool-proof, and are proving insufficient. Combining them with circumcision maximises protection.

c) Ignorance and disbelief. Some people have never heard that circumcision has benefits. Others are simply not convinced that circumcision has sufficient health benefits to merit the procedure. In this last case, intactivists are doing real damage by fostering this belief. In Malawi, 35 % of participants in one study actually thought that circumcision increased risk of contracting HIV (Dionne & Poulin 2013). In fact, denialism has been a serious impediment in Malawi, to the detriment of its people (Parkhurst et al. 2015).

Discussion

The benefits of circumcision commence from the moment the penis has healed. A significant benefit for infants is a high level of protection from urinary tract infections (UTIs) (Singh-Grewal et al. 2005; Morris & Wiswell 2012) which, prior to antibiotics, were a leading cause of infant mortality (Zorc et al. 2005), and which still occasionally kill (Wiswell & Geshke 1989). They are now increasingly becoming resistant to antibiotics (Bryce et al. 2016), raising the spectre of a return to the dark days when some 20 % of infant deaths were attributable to this cause (Zorc et al. 2005).

Infant circumcision also protects against other non-sexually transmitted infections. These can affect infants, children and adults alike (e.g. balanitis, posthitis, candidiasis). Infant circumcision also prevents dermatological conditions (phimosis, paraphimosis, lichen sclerosis) which are, themselves, common reasons for circumcision at later ages. Early age circumcision, but not adult circumcision, is highly protective against penile cancer (Larke et al. 2011).

Some argue that the benefits of circumcision apply only to adults. However, as the above shows this is false. It is true of sexually transmitted infections. But even then one can argue that if the lad is already circumcised then it is guaranteed he will have protection from the moment he makes his sexual debut, rather than gambling that he might opt for circumcision in adulthood. If he did so opt, he might leave it too late.

Thus, infant circumcision confers a variety of benefits that apply throughout childhood. Leaving the procedure until maturity denies the boy those benefits and thus risks his health.

The points 1 to 7 above apply to infants either not at all, or much less than they do to adults, and so constitute significant barriers to adults getting circumcised, as we shall see. Points 8 & 9 can only be addressed through education, but that will never persuade everyone in cultures where hostility to circumcision is deeply entrenched. Point 10 (b & c) is contradicted by the science, and undermined by the fact that infant circumcision ensures the male has some protection in his youth before he settles down into a stable relationship.

Despite these barriers, even in traditionally non-circumcising regions, circumcision is being taken up, if sometimes slowly. Education is the key, though a slow and not always effective one when resisted by deeply entrenched, irrational beliefs. As discussed above there are clear, direct and immediate advantages to the infant and child from being circumcised, in addition to those the adult benefits from. For a more detailed, comprehensive discussion, see Morris et al. (2012).

This matters a lot. In fact in some countries it is the difference between life and death on a terrifying scale. As explained in the section on HIV, circumcision is vital in the war against this virus, and is being heavily promoted in the most blighted countries. Obviously, to maximize effectiveness, uptake needs to be as high as possible. Originally focusing on adults, it is now being extended to infants because one can achieve a much higher uptake this way (http://circfacts.org/general-information/#med4).

There are scores of studies on the acceptability of circumcision, and barriers to it. Most concentrate on Africa, but there are some also from Asia and the Caribbean, all non-circumcising cultures. A consistent feature is that when properly educated about circumcision (i.e., given scientifically accurate information, not intactivist propaganda) large numbers of men, even majorities, are favourably inclined towards the procedure, but many still will not get it done. Aside from culture and religion, the main reasons given for adults not getting circumcised are items 1 to 7 above.

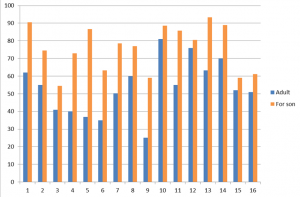

The Table summarizes commonly cited barriers to adult circumcision as reported in studies up to the end of 2017 (this review was conducted in early 2018). Most studies are qualitative, with small sample sizes, in which participants are asked about their concerns. In these cases a simple “Yes” indicates that some of the participants indicated that the barrier in question was of concern to them. Some of the larger studies gathered numerical data and were able to quantify what proportion of the participants would be deterred from a circumcision by the barrier in question. In these instances, the % who would be deterred is entered in the Table. If a space in the Table is blank it is because it either was not mentioned, or the study did not address it. Note how often items 1 to 7 above turn up.

Table: Findings from studies of barriers to adult circumcision

Key: 1 = Cost, 2 = Risk, 3 = Inconvenience, 4 = Need for sexual abstinence, 5 = Fear, 6 = Embarrassment, 7 = Cosmetic concerns, 8 = Cultural/religious objections, 9 = Concern about loss of sensation or function, 10 = Futility.

In the bottom row, “Total” is the total number of studies listed which identified the issue.

| Study | Country | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Notes |

| Adams & Moyer 2015 | Swaziland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | i | ||||||

| Albert et al. 2011 | Uganda | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Allen & Thomas-Purcell 2012 | Caribbean nations | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ii | |||||

| Bailey et al. 2002 | Kenya | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | iii | |||||

| Bengo et al. 2010 | Malawi | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Bulled & Green 2015 | Lesotho, Swaziland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Chikutsa & Maharaj 2015 | Zimbabwe | Yes | ||||||||||

| Chilimampunga et al. 2017 | Malawi | Yes | Yes | |||||||||

| Chiringa et al. 2016 | Zimbabwe | 58 | 84 | 58.5 | 89.7 | 58 | 68 | 86.8 | ||||

| Dionne & Poulin 2013 | Malawi | Yes | 30.3 | 0.7 | 86 | iv | ||||||

| Downs et al. 2013 | Tanzania | Yes | Yes | |||||||||

| Evens et al. 2014 | Kenya | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Feng et al. 2010 | China | Yes | Yes | |||||||||

| Figueroa & Cooper 2010 | Jamaica | 17 | ||||||||||

| Gasasira et al. 2012 | Rwanda | 42 | 11 | |||||||||

| George et al. 2014 | S. Africa | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Gonzales et al. 2012 | Columbia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | v | ||||||

| Hatzold, et al. 2014 | Zimbabwe | 3.5 | Yes | 50 | 17.3 | |||||||

| Herman-Roloff et al. 2011 | Kenya | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Hoffman et al. 2015 | S. Africa | 24.5 | 42.9 | Yes | 44.9 | Yes | 28.6 | |||||

| Jiang et al. 2013 | China | 10.7 | 18.5 | 13.2 | 62.6 | |||||||

| Jiang et al. 2015 | China | 14.8 | 34.7 | 18.8 | 4.2 | |||||||

| Khumalo & Greene 2010 | Swaziland | Yes | Yes | |||||||||

| Kuhamalo-Sakutukwa et al. 2013 | Zimbabwe & S. Africa | Yes | Yes | |||||||||

| Kong et al. 2014 | Uganda | 45.8 | Yes | Yes | 66.3 | 5.5 | Yes | 12.1 | ||||

| Lukobo & Bailey 2007 | Zambia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Macintyre et al. 2014 | Kenya | Yes | Yes | |||||||||

| Maibvise & Mavundla 2014 | Swaziland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Marshall et al. 2016 | S. Africa | 20 | 17.8 | 0.5 | 20 | 0.5 | 32.5 | 2.7 | vi | |||

| Marshall et al. 2017 | S. Africa | 39.4 | ||||||||||

| Mattson et al. 2005 | Kenya | 34 | 40 | |||||||||

| Moyo et al. 2015 | Zimbabwe | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Nevin et al. 2015 | Uganda | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | vii | ||||||

| Ngalande et al. 2006 | Malawi | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Nyaga et al. 2014 | Kenya | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Plotkin et al. 2013 | Tanzania | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Ruan et al. 2009 | China | 12.7 | 46.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 7.0 | 28.5 | viii | ||||

| Scott et al. 2005 | S. Africa | Yes | Yes | 46.8 | 11.7 | |||||||

| Skolnik et al. 2014 | Lesotho | 17 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 56.5 | 18 | ||||||

| Ssesekubugu et al. 2013 | Uganda | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Wang et al. 2016 | China | 9.7 | 32.1 | 35.1 | 20.7 | 36.9 | ||||||

| Westercamp et al. 2012 | Kenya | 2 | 2 | 23 | 20 | 7 | ix | |||||

| Yang et al. 2012 | China | 5.7 | 13.2 | Yes | 10.4 | 81.1 | ||||||

| Zamawe & Kusamula 2015 | Malawi | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Total | World | 24 | 27 | 10 | 16 | 26 | 8 | 3 | 26 | 20 | 18 |

Notes

i. Participants expressly denied that fear of pain would deter them. This was linked to their concept of masculinity. A masculine person would not be deterred by pain.

ii. Nations were: Dominica, Grenada, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

iii. Lack of access to health facilities was also cited as a barrier in this study conducted prior to the circumcision campaign. Despite the reported barriers, a majority still approved of circumcision.

iv. Only 14 % thought circumcision would protect them against HIV, 35 % thought it would increase their risk.

v. A study of gay & bisexual men.

vi. Items 2 & 5 (risk & fear) were 20 % combined.

vii. Participants perceived infant circumcision as preferable as it avoided some of the barriers.

viii. A study of gay & bisexual men. Data for item 9 taken from Table 1 in the source and is for concern about effect on pleasure for the circumcised man only. 37.7 & 27.8 % thought circumcision would have no effect on their or their partner’s pleasure, respectively. 12 % were concerned it would have a negative effect on their partner’s pleasure. The remainder were “Don’t know”.

ix. Figures are for men who were not circumcised but wanted to be. 23 % complained “the process takes too long” which is interpreted here as “inconvenience” (item 3).

Culture, risk of complications, fear of pain and cost are the most frequently cited barriers. The latter three are greatly mitigated for infants as explained previously. Other issues that apply to infants either much less or not at all (items 1 to 7) are also commonly cited. Thus it is no surprise that, consistently, one can achieve far higher uptakes (sometimes > 90 %) with infant/childhood circumcision than one can with adult (see: http://circfacts.org/general-information/#med4).

In a situation where it is imperative to get uptake as high as possible to curb a devastating pandemic, infant circumcision is absolutely vital in the long term. Delaying circumcision until adulthood is massively counter-productive. It just means a cohort of young men who would not mind being circumcised, or might even want it, but will be deterred by the aforementioned barriers. They are therefore vulnerable. Inevitably some will end up infected, and will pass the infection on. Over enough time it will mean millions more infections that could so easily have been avoided. This would be the result of following the intactivists’ doctrinaire insistence on choice and “bodily autonomy”.

As an indication of the dogmatic rigidity of the thought processes of intactivists, even when they know of the potential for disaster they still oppose infant circumcision. Matthew Hess, a leader in the San Francisco Bay area, was quoted as saying (Oltman 2011):

“Even if it could be shown that circumcision provided 100 percent protection against AIDS, I would still be opposed to forcing that onto a child who can’t consent.”

Sadly, even some in the sceptical movement who, one might hope, would follow the science rather than their emotions, take the same view. Myles Power, an English skeptic with a huge YouTube following, accepts the science but still dogmatically elevates “choice” above saving lives (Power 2017):

“I understand the risks with circumcision increase with age, and the fact that most young men probably won’t want to get a sensitive part of their body cut, which will more than likely, in certain parts of the world, result in more people being infected with HIV, but that I believe that it’s the boy/man’s right to choose what happens to his body.”

Or, to put it bluntly, science-based medicine saves lives. Intactivist ideology kills. In the topsy-turvy world of intactivists and their sympathisers, the latter is considered ethical.

References

Adams, A., Moyer, E. (2014). Sex is never the same: Men’s perspectives on refusing circumcision from an in-depth qualitative study in Kwaluseni, Swaziland. Global Public Health, 10(5-6), 721-38. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25654269

Albert, L.M., Akol, A., L’Engle, K., Tolley, E.E., Ramirez, C.B., Opio, A., Tumwesigye, N.M., Thomsen, S., Neema, S., Baine, S.O. (2011) Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV infection among men and women in Uganda. AIDS Care, 23(12), 1578-85. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21732902

Allen, C., Thomas-Purcell, K.B. (2014) Strengthening the evidence base on youth sexual and reproductive health and rights in the eastern Caribbean. UNFPA Report. On-line: http://caribbean.unfpa.org/en/publications/strengthening-evidence-base-youth-sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights-eastern-0

Bailey, R.C., Muga, R., Poulussen, R., Abicht, H. (2002) The acceptability of male circumcision to reduce HIV infections in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Care, 14(1), 27-40. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11798403

Bengo, J.M., Chalulu, K., Chinkhumba, J., Kazembe, L., Maleta, K.M., Masiye, F., Mathanga, D., (2010) Situation analysis of male circumcision in Malawi. Draft report by College of Medicine. On-line: http://ndr.mw:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/965/Situation%20analysis%20of%20male.pdf?sequence=1

Bulled, N., Green, E.C. (2015) Making voluntary medical male circumcision a viable HIV prevention strategy in high-prevalence countries by engaging the traditional sector. Critical Public Health, 26(3), 258-68. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4837468/

Binagwaho A, Pegurri E, Muita J, Bertozzi S (2010) Male circumcision at different ages in Rwanda: A cost-effectiveness study. PLoS Med., 7(1): e1000211. On-line: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000211

Bryce, A., Hay, A.D., Lane, I.F., Thornton, H.V., Wootton, M., Costelloe, C. (2016) Global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in paediatric urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli and association with routine use of antibiotics in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 352, On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4793155/

Chikutsa, A., Maharaj, P. (2015) Social representations of male circumcision as prophylaxis against HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health, 15(603). On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4489047/

Chilimampunga, C., Lijenje, S., Sherman, J., Nindi, K., Mavhu, W. (2017) Acceptability and feasibility of early infant male circumcision for HIV prevention in Malawi. PLoS One, 12(4):e0175873. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5393613/

Chinkhumba, J., Godlonton, S., Thornton, R. (2012) Demand for medical male circumcision. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(2), 152-7. On-line: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/app.6.2.152

Chiringa, I.O., Ramathuba, D.U. Mashau, N.S. (2016) Factors contributing to the low uptake of medical male circumcision in Mutare Rural District, Zimbabwe. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 8(2), e1-6. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4913440/

Dionne, K.Y., Poulin, M. (2013) Ethnic identity, region and attitudes towards male circumcision in a high HIV-prevalence country. Global Public Health, 8(5), 607-18. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3706459/

Downs, J.A., Fuunay, L.D., Fuunay, M., Mbago, M., Mwakisole, A., Peck, R.N., Downs, D.J. (2013) ‘The body we leave behind’: A qualitative study of obstacles and opportunities for increasing uptake of male circumcision among Tanzanian Christians. BMJ Open. 3(5), e002802. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3657636/

El Bcheraoui, C., Zhang, X., Copper, C.S., Rose, C.E., Kilmarx, P.H., Chen, R.T. (2014) Rates of adverse events associated with male circumcision in US medical settings, 2001 to 2010. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(7), 625-34. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4578797/

Evens, E., Lanham, M., Hart, C., Loolpapit, M., Oguma, I., Obiero, W. (2014) Identifying and addressing barriers to uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision in Nyanza, Kenya among men 18–35: A qualitative study. PLoS One, 9(6), e98221. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4047024/

Feng, N., Lu, F., Zeng, G., Nan, L., Wang, X.Y., Xu, P., Zhang, J.X., Zhang S.E. (2010). Acceptability and related factors on male circumcision among young men with Yi ethnicity in one county of Sichuan province. [In Chinese]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi, 31(3), 281–285. On-line English abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20510053

Figueroa, J.P., Cooper, C.J. (2010) Attitudes towards male circumcision among attendees at a sexually transmitted infection clinic in Kingston, Jamaica. West Indian Med. J., 59(4), 198-202. On-line: http://caribbean.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0043-31442010000400003

Gasasira, R.A., Sarker, M., Tsague, L., Nsanzimana, S., Gwiza, A., Mbabazi, J., Karema, C., Asiimwe, A., Mugwaneza, P. (2012) Determinants of circumcision and willingness to be circumcised by Rwandan men, 2010. BMC Public Health, 12(134). On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3299639/

George, G., Strauss, M., Chirawu, P., Rhodes, B., Frohlich, J., Montague, C., Govender, K. (2014) Barriers and facilitators to the uptake of voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) among adolescent boys in KwaZulu–Natal, South Africa. African J. AIDS Res., 13(2), 179-87. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25174635

Gonzales, F.A., Zea, M.C., Reisen, C.A., Bianchi, F.T., Rodríguez, C.F.B., Pardo, M.A., Poppe, P.J. (2012) Popular perceptions of circumcision among Colombian men who have sex with men. Cult. Health Sex., 14(9), 991-1005. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3463718/

Hatzold, K., Mavhu, W., Jasi, P., Chatora, K., Cowan, F.M., Taruberekera, N., Mugurungi, O., Ahanda, K., Njeuhmeli, E. (2014) Barriers and motivators to voluntary medical male circumcision uptake among different age groups of men in Zimbabwe: Results from a mixed methods study. PLoS One, 9(5):e85051. On-line: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0085051

Herman-Roloff, A., Otieno, N., Agot, K., Ndinya-Achola, J., Bailey, R.C. (2011) Acceptability of medical male circumcision among uncircumcised men in Kenya one year after the launch of the national male circumcision program. PLoS One, 6(5), e19814. On-line: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0019814

Hoffman, J.R., Arendse, K.D., Larbi, C. Johnson, N., Vivian, L.M.H. (2015) Perceptions and knowledge of voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in traditionally non-circumcising communities in South Africa. Global Public Health, 10(5-6), 692-707. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25727250

Jiang, J., Huang, J., Yang, X., Ye, L., Wei, B., Deng, W., Weu, S., Qin, B., Upur, H., Zhong, C., Wang, Q., Wang, Q., Ruan, Y., Wei, F., Xu, N., Xie, P., Liang, H. (2013) Acceptance of male circumcision among male rural-to-urban migrants in Western China. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses, 29(12), 1582-8. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3848437/

Jiang, J., Su, J., Yang, X., Huang M., Deng, W., Huang, J., Liang, B., Qin, B., Upur, H., Zhong, C., Wang, Q., Wang, Q., Ruan, Y., Ye, L., Liang, H. (2015) Acceptability of male circumcision among college students in medical universities in Western China: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One, 10(9): e0135706. On-line: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0135706

Khumalo, P., Greene, J. (2010) Swaziland (2010): Male circumcision TRaC study evaluating the use of male circumcision among males aged 13-29 years in rural and urban Swaziland. PSI TRaC Summary Report. On-line: https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/2010-swaziland_trac_hiv_ml_mc.pdf

Kuhamalo-Sakutukwa, G., Lane, T., van-Rooyen, H., Chingono, A., Humphries, H., Timbe, A., Fritz, K., Chirowodza, A., Morin, S.F. (2013) Understanding and addressing sociocultural barriers to medical male circumcision in traditionally noncircumcising rural communities in sub-Saharan Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(9), 1085-100. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3810456/

Kong, X., Ssekasanvu, J., Kigozi, G., Lutalo, T., Nalugoda, F., Serwadda, D., Wawer, M., Gray, R. (2014) Male circumcision coverage, knowledge, and attitudes after 4-Years of program scale-up in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Behav., 18(5), 880-4. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/24633740/

Larke, N.L., Thomas, S.L., dos Santos, I., Weiss, H.A. (2011) Male circumcision and penile cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control, 22(8), 1097-110. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3139859/

Lukobo, M.D., Bailey, R.C. (2007) Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV infection in Zambia. AIDS Care, 19(4), 471-7. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17453585

Macintyre, K., Andrinopoulos, K., Moses, N., Bornstein, M., Ochieng, A., Peacock, E., Bertrand, J. (2014) Attitudes, perceptions and potential uptake of male circumcision among older men in Turkana County, Kenya using qualitative methods. PLoS One, 9(5):e83998. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4011674/

Maibvise, C., Mavundla, T.R. (2014) Reasons for the low uptake of adult male circumcision for the prevention of HIV transmission in Swaziland. African J. AIDS Res., 13(3), 281-9. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25388982

Marshall, E., Rain-Taljaard, R., Tsepe, M., Monkwe, C., Hlatswayo, F., Tshabalala, S., Khela, S., Xulu, L., Xaba, D., Molomo, T., Malinga, T., Puren, A., Auvert, B. (2016) Sequential cross-sectional surveys in Orange Farm, a township of South Africa, revealed a constant low voluntary medical male circumcision uptake among adults despite demand creation campaigns and high acceptability. PLoS One, 11(7): e0158675. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4948820/

Marshall, E., Rain-Taljaard, R., Tsepe, M., Monkwe, C., Taljaard, D., Hlatswayo, F., Xabac, D., Molomo, T., Lissouba, P., Puren, A., Auvert, B. (2017) Obtaining a male circumcision prevalence rate of 80% among adults in a short time: An observational prospective intervention study in the Orange Farm township of South Africa. Medicine (Baltimore), 96(4):e5328. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5287938/

Mattson, C.L., Bailey, R.C., Muga, R., Poulussen, R., Onyango, T., (2005) Acceptability of male circumcision and predictors of circumcision preference among men and women in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Care, 17(2), 182-94. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15763713

Mavhu,W., Hatzold, K., Ncube, G., Fernando, S., Mangenah, C., Chatora, K., Mugurungi, O., Ticklay, I., Cowan, F.M. (2016) Perspectives of parents and health care workers on early infant male circumcision conducted using devices: Qualitative findings from Harare, Zimbabwe. Global Health: Science & Practice, 4, Supplement 1, S55-67: On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4944580/

Morris, B.J., Waskett, J.H., Banerjee, J., Wamai, R.G., Tobian, A.A.R., Gray, R.H., Bailis, S.A., Bailey, R.C., Klausner, J.D., Willcourt, R.J., Halperin, D.T., Wiswell, T.E., Mindel, A. (2012) A ‘snip’ in time: what is the best age to circumcise? BMC Pediatrics, 12(20). On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3359221/

Morris, B.J., Wiswell, T.E. (2012) Circumcision and lifetime risk of urinary tract infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Urol., 189(6), 2118-24. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23201382

Moyo, S., Mhloyi, M., Chevo, T., Rusinga, O. (2015) Men’s attitudes: A hindrance to the demand for voluntary medical male circumcision – A qualitative study in rural Mhondoro-Ngezi, Zimbabwe. Global Public Health, 10(5-6), 708-20. On line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25648951

Nevin, P.E., Pfeiffer, J., Kibira, S.P.S., Lubinga, S.J., Mukose, A., Babigumira, J.B. (2015) Perceptions of HIV and safe male circumcision in high HIV prevalence fishing communities on Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS One, 10(12), e0145543. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4686987/

Ngalande, R.C., Levy, J., Kapondo, C.P.N., Bailey, R.C. (2006) Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV infection in Malawi. AIDS Behav., 10(4), 377-85. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16736112

Njeuhmeli, E. (2014) Cost and Impact of Scaling Up EIMC in Southern and Eastern Africa using the DMPPT 2.0 Model. PEPFAR PowerPoint presentation. On-line: https://www.malecircumcision.org/resource/cost-and-impact-scaling-eimc-southern-and-eastern-africa-using-dmppt-20-model

Nyaga, E.M., Mbugua, C.G., Muthami, L., Gikunju, J.K. (2014) Factors influencing voluntary medical male circumcision among men aged 18-50 years in Kibera division. East Afr. Med. J., 91(11), 407-13. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26866089

Oltman, S. (2011) Holy Scalpels, Foreskin Man! Mother Jones, 2 August. On-line: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2011/08/sf-circumcision-ban-matthew-hess-foreskin-man-comic/

Parkhurst, J.O., Chilongozi, D., Hutchinson, E. (2015) Doubt, defiance, and identity: Understanding resistance to male circumcision for HIV prevention in Malawi. Social Science & Medicine, 135, 15-22. On-line: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S027795361500249X?via%3Dihub

Plotkin, M., Castor, D., Mziray, H., Küver, J., Mpuya, E., Luvanda, P.J., Hellar, A., Curran, K., Lukobo-Durell, M., Ashengo, T.A., Mahler, H. (2013) ‘‘Man, what took you so long?’’ Social and individual factors affecting adult attendance at voluntary medical male circumcision services in Tanzania. Glob. Health Sci. Pract., 1(1), 108-16. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4168557/

Power, M. (2017) Top Ten Myles Power F**k Ups. Blog post 1 December. On-line: https://mylespower.co.uk/2017/12/01/top-ten-myles-power-fk-ups/ (scroll to item 9).

Ruan, Y., Qian, H-Z., Li, D., Shi, W., Li, Q., Liang, H., Yang, Y., Luo, F., Vermund, S.H., Sha, Y. (2009) Willingness to be circumcised for preventing HIV among Chinese men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(5), 315–321. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2743100/

Scott, B.E., Weiss, H., Viljoen, J.I. (2005) The acceptability of male circumcision as an HIV intervention among a rural Zulu population, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care, 17(3), 304-13. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15832878

Singh-Grewal, D., Macdessi, J., Craig, J. (2005) Circumcision for the prevention of urinary tract infection in boys: a systematic review of randomised trials and observational studies. Arch. Dis. Child., 90(8), 853–858. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1720543/

Skolnik, L., Tsui, S., Ashengo, T.A., Kikaya, V., Lukobo-Durrell, M. (2014) A cross-sectional study describing motivations and barriers to voluntary medical male circumcision in Lesotho. BMC Public Health, 14(1119). On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4287583/

Ssesekubugu, R., Leontsini, E., Wawer, M.J., Serwadda, D., Kigozi, G., Kennedy, C.E., Nalugoda, F., Sekamwa, R., Wagman, J., Gray, R.H. (2013) Contextual barriers and motivators to adult male medical circumcision in Rakai, Uganda. Qual. Health Res., 23(6), 795-804. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23515302

Wang, Z., Feng, T., Lau, J.T.F., Kim, Y. (2016) Acceptability of voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) among male sexually transmitted diseases patients (MSTDP) in China. PLoS One, 11(2):e0149801. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4764373/

Westercamp, M., Agot, K.E., Ndinya-Achola, J., Bailey, R.C. (2012) Circumcision preference among women and uncircumcised men prior to scale-up of male circumcision for HIV prevention in Kisumu, Kenya. AIDS Care, 24(2), 157-66. On line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3682798/

Wiswell, T.E. Geshke, D.W. (1989) Risks from circumcision during the first month of life compared to those for uncircumcised boys. Pediatrics, 83(6), 1011-5. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2562792

Yang, X., Abdullah, A.S., Wei, B., Juang, J., Deng, W., Qin, B., Yan, W., Wang, Q., Zhong, C., Wang, Q., Ruan, Y., Zou, Y., Xie, P., Wei, F., Xu, N., Liang, H. (2012) Factors influencing Chinese male’s willingness to undergo circumcision: A cross-sectional study in Western China. PLoS One, 7(1):e30198. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3257276/

Zamawe, C.O.F., Kusamula, F. (2015) What are the social and individual factors that are associated with undergoing male circumcision as an HIV prevention strategy? A mixed methods study in Malawi. Int. Health, 8(3), 170-8. On-line abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26503362

Zorc, J.J., Kiddoo, D.A., Shaw, K.N. (2005) Diagnosis and management of pediatric urinary tract infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 18(2), 417-22. On-line: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1082801/

Men rarely choose to be circumcised

March 2018

The idea behind this common assertion is an implication that men value their foreskins so highly that few would wish to part with theirs’, or that if infants could express a wish they’d say, “No”. For example:

“Because competent males rarely choose to be circumcised, CPs [circumcision proponents] have recommended that infants be circumcised … If the benefits of circumcision were compelling, competent people would choose it. … Given that adolescent and adult males rarely choose to be circumcised … it can be inferred that the infant would not choose circumcision if competent” (Van Howe 2013).

The statement is also false, as is so often the case with intactivist claims. By the time Van Howe made these assertions half a million African men had already volunteered for circumcision as part of the WHO-backed Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision (VMMC) program to combat the spread of HIV. At that time the VMMC program was just getting under way. The numbers soared in the following years. By 2016, over 14.5 million African youths and men had volunteered to be circumcised (WHO 2017). That’s an average of 1.8 million a year, and rising (it was actually 2.8 million in 2016).

It also betrays ignorance as to the reasons many adults decline circumcision. It is not that they don’t want it, it is because having it done later in life is daunting, with many barriers to overcome (http://circfacts.org/general-information/#med3). It takes determination and courage to overcome these barriers, barriers which often apply less, if at all, to infants. And, in the absence of HIV, many don’t have a strong enough incentive to make the effort.

It seems that seeing ones’ friends, neighbours and colleagues dying of a horrible disease that can be prevented by removing the foreskin has a salutary effect. Couple this with good education and availability, and many men will avail themselves of the procedure. Kenya has been particularly successful in meeting, even exceeding targets, thanks to a combination of dire necessity and good leadership (Okeyo 2016).

But not all countries have been able to emulate this success and, overall, the African circumcision program is falling short of the initial targets. Simply put, even when men see the benefits of being circumcised and are positive about the idea, many will still not have it done. Sometimes the difference between the number of men expressing support for the procedure, and the number actually having it done can be stark. In Swaziland, for example, despite studies indicating that as many as 72.4 % or 87 % of males were positive about circumcision, less than 6 % of 150,000 men targeted actually underwent the procedure (Adams & Moyer 2015).

In Malawi, 80.8 % of men questioned were initially opposed to the procedure. On being informed of the benefits this declined to 63.2 %, with 36.8 % now favouring it (Bengo et al. 2010). Another study in Malawi at about the same time found 47.6 % willing to be circumcised (Chinkhumba et al. 2012), rising to 61 % for men who “contemplated” it over the following year. But being accepting of circumcision does not necessarily translate into getting it done. In that second study, 1,634 Malawian men were recruited. A year later, of the 1,252 men who returned for interview, only 111 (8.9 %) had been circumcised in the interim despite it being offered for free, or heavily subsidised.

Doubtless many of those men will have got circumcised eventually, after the studies concluded, but there is still a marked shortfall between numbers saying they are willing, and numbers actually getting it done. The disparity is for reasons explained here: http://circfacts.org/general-information/#med3

That men do not often seek “the snip” outside of HIV epidemic settings can be put down to a combination of ignorance, lack of familiarity and lack of availability. In countries where there is no HIV epidemic, there is very much less pressure to promote the procedure, so it is not happening, and private clinics that do offer it are expensive. With no culture of circumcision, men are simply unfamiliar with it. It is something foreign, that religious groups do, and not for them. So, the typical response in countries where circumcision is uncommon, and there is no education about it, is a knee-jerk one. After all, the default position is to have a foreskin, and men are generally protective of their genitals. Accordingly, any suggestion of cutting such a psychologically, as well as physically, “sensitive” region will likely result in an instinctive rejection.

But two things can counter that: familiarity and education. In countries where circumcision is common, opposition is much less, and not just where it is a religious requirement. Circumcision is very common in the USA, but is not universal. A YouGov poll of American men asked them if they were happy about their circumcision status. Only 10 % of the circumcised men expressed dissatisfaction with their absence of foreskin, but 29 % of the non-circumcised men wished they were circumcised (YouGov 2015). Men familiar with circumcision, are more receptive to the idea.

When educated about the benefits of circumcision, i.e. provided with scientifically accurate information, not the lies and propaganda of intactivists, something interesting happens. In non-circumcising cultures, men who previously would not have considered the procedure (after all, they live in non-circumcising cultures) often become positive about the idea. In fact, commonly majorities become positive about it. That some don’t, and that many of those who are positive nevertheless decline to get it done, can be attributed to the barriers to getting it done. Culture and religion remain major obstacles, but most barriers are unrelated, and are described in the link above.

As many of those barriers (need for time off work, sexual abstinence during healing, etc.) do not apply to infants or children, when parents are asked if they would have a son circumcised, even higher proportions become positive about the idea. We know this because a great deal of research has been done investigating it. After all, if the WHO and other medical bodies are going to promote circumcision, they need to know if it will be accepted, and what factors may act as barriers to uptake.

The majority of these studies have focused on Africa, where the HIV epidemic is at its worst, but a few have looked at the Caribbean and parts of Asia and the Far East. All were in non-circumcising cultures – there being no point investigating the acceptability of circumcision in a culture that already accepts and practices it.

The Table below summarizes the findings of those studies (up to end of 2017) that actually quantified acceptability (in % terms). Included are data from over 40 studies, encompassing 15 countries across the globe, conducted by independent teams of researchers. The findings of these studies are consistent with each other – replication is an important part of science.

Table. Results from circumcision acceptability surveys

Key: Before = before receiving counselling about circumcision’s benefits as part of the study (although the participants had often already learned of it from other sources).

After = after being given counselling about circumcision’s benefits in the course of the study.

If the study did not attempt to counsel the participants about circumcision’s benefits, but merely solicited their views, then the results are entered in the “Before” column.

Preferred age for a son’s circumcision (if stated): I = infancy, C = childhood, A = adolescence, G = grown up (age 18+). For those who would circumcise a son, the %s preferring particular ages are indicated if those data are available, e.g. “I 27–67” means 27 to 67 % preferred infancy.

| Study | Country | % of men positive about getting circumcised | % of fathers willing to circumcise a son | % of mothers willing to circumcise a son | % women preferring circ’d men | Notes | |||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | ||||

| Albert et al. 2011 | Uganda | 40-62 | 60-86 I 15-55 C 36-43 A 5-29 G 1-9 |

49-95 I 27-67 C 16-36 A 7-26 G 4-15 |

i | ||||

| Ansari et al. 2017 | Indonesia | 26.8 | ii | ||||||

| Bengo et al. 2010 | Malawi | 19.2 | 36.8 | 26.6 | 79.8 I 11.3 C 62.9 A 16.7 |

43.3 | 93.6 | ||

| Chinkhumba et al. 2012 | Malawi | 47.6 – 61 | iii | ||||||

| Feng et al. 2010 | China | 40.6 | |||||||

| Figueroa & Cooper 2010 | Jamaica | 35-48 | 54 | 72.4 | 67.3 | iv | |||

| Gasasira et al. 2012 | Rwanda | 50.2 |

78.5 |

||||||

| Halperin et al. 2005 | Zimbabwe | 45 | |||||||

| Hatzold et al. 2014 | Zimbabwe | 60 | 75.9 | 77.9 | 71.7 | v | |||

| Hoffman et al. 2015 | S. Africa | 49 | vi | ||||||

| Huang et al. 2016 | China | 41.9 | 60.7 | vii | |||||

| Hudson et al. 2017 | Kenya | 25 | 59 | ||||||

| Ikwegbue et al. 2015 | S. Africa | 83.7 | 82.4 | viii | |||||

| Jarrett et al. 2014 | Swaziland | 100 | ix | ||||||

| Jiang et al. 2013 | China | 37.3 | 69.6 | x | |||||

| Jiang et al. 2015 | China | 55.2 | xi | ||||||

| Kebaabetswe et al. 2003 | Botswana | 61 | 81 | 67 | 87 | 62 | 90 | 79 | xii |

| Keetile & Bowelo 2016 | Botswana | 55 | 83.5 | 88.1 | xiii | ||||

| Khumalo & Greene 2010 | Swaziland | 72.4 | xiv | ||||||

| Kong et al. 2014 | Uganda | 27.3 | |||||||

| Lagarde et al. 2003 | S. Africa | 72.5 | |||||||

| MacLaren et al. 2013 | Papua New Guinea | 76 | 87 | 74 | xv | ||||

| Madhivanan et al. 2009 | India | 88 | xvi | ||||||

| Maraux et al. 2011 | S. Africa | 95.8 | 73.7 | xvii | |||||

| Marshall et al. 2016 | S. Africa | 63.2 | 93.4 – 99.7 |

xviii | |||||

| Marshall et al. 2017 | S. Africa | 87.7 | xix | ||||||

| Mattson et al. 2005 | Kenya | 60 – 70 | 89 | 69 | xx | ||||

| Mavhu et al. 2011 | Zimbabwe | 52 | I 57.7 | I 60.3 | 58 | ||||

| Mndzebel & Tegegn 2014 | Botswana | 64.5 | |||||||

| Mugwanya et al. 2011 | Uganda | 90.2 I 65.1 C 29.9 A 4.4 |

94.6 |

||||||

| Nyaga et al. 2014 | Kenya | 84 I 10 C 39 A 41 G 12 |

xxi | ||||||

| Pan et al. 2012 | China | 40.8 | 26.2 | xxii | |||||